I have jumped out of aeroplanes, mountain-biked the world’s most dangerous roads, surfed following seas at 15 knots, and hit storms off Africa that had crew throwing up, but nothing could have prepared me for the four days of hell Liz and I just endured.

You see it wasn’t the weather itself that terrified us, it was the situation we found ourselves in after the first squall hit. We entered the Twilight Zone, and for four days got trapped in an increasingly desperate situation.

The Scenario

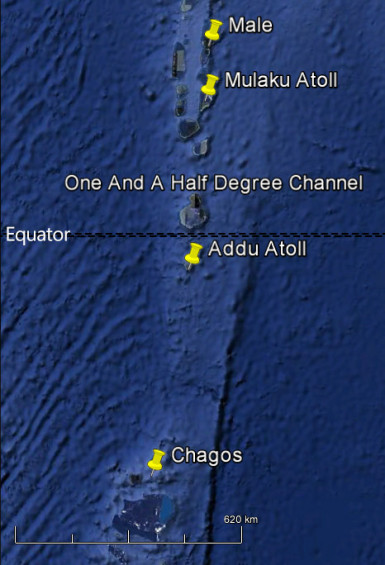

With just seven days to go before our cruising permit ran out we had to make the 350 mile trip to Gan on the southern-most atoll of Addu. Once there we would provision, refuel, fill up our water tanks and check out of the Maldives to continue south a further 300 or so miles to Chagos, where we would spend a few weeks before heading west to Madagascar.

With just seven days to go before our cruising permit ran out we had to make the 350 mile trip to Gan on the southern-most atoll of Addu. Once there we would provision, refuel, fill up our water tanks and check out of the Maldives to continue south a further 300 or so miles to Chagos, where we would spend a few weeks before heading west to Madagascar.

Esper’s cruising speed is roughly 6 knots, so we average around 120 miles or so over a 24 hour period, providing the weather is on our side. Under engine she’s slower, and motoring into wind, tide or current our speed easily reduces to 2 knots or fewer.

The Weather

We are now in the transitional period, which is the precursor to the South West monsoon. Winds and stormy weather build during this period.

We were monitoring big lows building on both sides of the equator. To the south, cyclones (hurricanes) travel west and rotate in a clock-wise direction; on the north side it’s the opposite. Both of these effect the weather in the surrounding regions and dictate where vessels can and cannot go. Travelling too early over the equator would be dangerous, travelling too late we could miss our window, so timing is important.

Either side of the equator are equatorial currents. The Northern Equatorial Current travels from west to east, the Southern Equatorial Current from east to west. These can either help or hinder progress, so angles of attack become important features of passage planning.

The Start

We left Male with SY Divanty and had a cracking sail south, arriving in Muli Lagoon on Mulaku atoll a day later. Anchoring turned out to more difficult here than anywhere else in the Maldives, but that’s another story…

The inhabited island of Naalaafushi was a delight as we watched local kids taking part in ‘Children’s Day 2013’, putting on a fashion show, singing and dancing, all to the delight of proud parents and grinning spectators.

To make up some time, our next trip was to take us east past the next atolls of Kolhumadulu and Hadhdhunmathee and onto North Huvadhoo, the penultimate atoll before Addu.

To make up some time, our next trip was to take us east past the next atolls of Kolhumadulu and Hadhdhunmathee and onto North Huvadhoo, the penultimate atoll before Addu.

We had planned to sail west of Hadhdhunmathee atoll but south-western winds put paid to that plan. Still, the forecast was westerlies so they should see us right for the crossing. Either way, we had to make the passage from the east to west at some point between the atolls.

Once at sea and checking the conditions, we agreed to go east of Hadhdfhunmathee atoll, along the southern side, which is protected somewhat by reefs. We would get over as far west as possible before dropping south.

We’d have preferred to have gone through the atolls but this requires eye ball navigation through shoals and bommies (columns of coral), possible during the day only, and time was not on our side.

We ate our pre-prepared pasta salad and within a couple of hours I was on the toilet with bum wee. I’d picked up a bug from somewhere and started feeling ill. This was not a good start and it was the beginning of my four-day diet, one that I wouldn’t recommend to anyone.

Squall One

As night fell Antony of SY Divanty radioed through on the VHF

“Esper, Esper, this is Divanty. Do you copy? Over”.

“Divanty, this is Esper. Go ahead.”

“You’re cracking along there, Esper. Do you plan to reef down (reduce sail) for the night? Over.”

“No, I don’t think so, Ants. We have one reef in and are in the lee of this atoll (meaning the atoll protects us from building seas and current).”

Mistake number one.

As we came round the south-east corner of Hadhdhunmathee atoll we tucked in towards land. Things seemed to be going well. We were close-hauled (sailing in to wind) and the winds were coming round to the west, so we had a good angle of attack for the next passage, which would take us into the One and a Half Degree Channel. Since the channel travels from west to east we had to get as far west as possible.

Antony’s voice strained on the VHF radio. Breaking the usual radio protocol he just said:

“Esper, THERE IS A SQUALL COMING. It’s a big one, at least 26 knots.”

We’ve since checked Divanty’s wind instruments and found them to be four knots out. Unfortunately they read four knots slower than actual wind speed, so we were about to be hit by winds rated a Force Seven, near gale conditions.

On a good day squalls are easy to spot. In daylight the clouds darken and you can see the change in sea state, there’s usually a white wall of water heading at you. At night if nothing else you can monitor the wind speed and see it pick-up steadily before the shit hits the fan. We had no such warning except Anthony’s, which gave us a few vital extra seconds.

At the time Liz was helming and I was at the back of the boat, about to engage our auto-pilot (an hydraulic ram that steers an auxiliary rudder so we don’t have to steer manually). I just had time to disengage the thing and get back to the cockpit before 30 knots of wind hit Esper square on.

“You know what to do, Liz”, I said, as I clambered back to the cockpit, hearing the winds whistling through the rigging.

She’d done this before and I had complete faith in my helmswoman, but it still didn’t stop the adrenaline rush as the boat began to heel.

Almost immediately it arrived. Bang! We were hit by howling winds and hard rain, and Esper tipped over.

Liz clung to the wheel, keeping Esper into wind as best as possible while the warm Indian Ocean came over the side.

“I think we need to reef”, suggested a deadpan Liz.

Nice to see my crew keeping their spirits up in hairy conditions, I thought! She was right, though, we had too much sail out. Although the boat was balanced and Liz wasn’t fighting the wheel, Esper was heeling far too much for my liking. Allowing winds and waves to hit the boat from the side could be dangerous and would have pushed us off-course, so steering her into the wind was crucial. An alternative would have been to go down-wind, putting the winds behind us, but that would have taken us into open sea and to the point of no return.

I attempted to reef the mizzen (the rear sail) first and instead of furling her away, the furling line slipped and the whole sail came out, ripping my hands in the process. This pushed Esper into wind so now Liz had to battle to keep her from tacking (putting the wind on the other side of the boat).

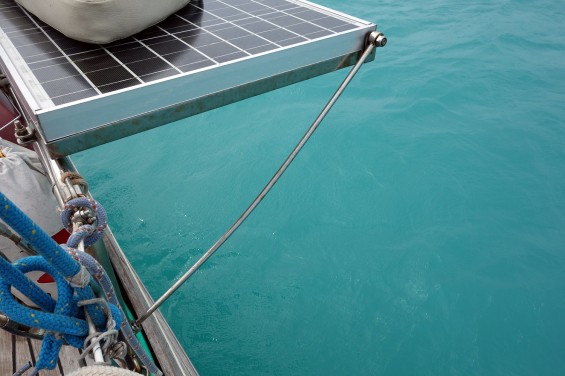

With Esper tipping up even further I was clinging to the mizzen mast, looking down at the solar panels that I had stupidly left out. Normally mounted so they are at 90 degrees when upright, they were now in the water! We were healing so much the water level was rushing into the cock-pit, situated at the centre of the boat. I’d never seen Esper lean over so far, and we’ve sailed in some pretty strong winds. We must have broached but there was too much rain to see.

“Just keep pointing into wind”, I shouted, the rain slashing at my face.

Liz, a hunched bundle of waterproof oilies, just nodded and kept her eyes fixed on the wind instrument. We gradually came up, but were still dangerously leaning. The winds were getting stronger now, gusting Force Eight.

A gale.

With vicious rain there was no visibility and Liz could only steer by the wind instrument. I had to let the mizzen sheet (rope) go, to de-powered the sail.

“You need to reef the front sails!”, Liz shouted, without turning.

As if I didn’t know that!

“Just keep that boat into wind!”, I replied, trying to figure out how to let out a bit of sail in order to then furl it away.

Normally the stay-sail (this is a smaller, inner sail at the front that helps steer a boat when going into wind) is easy to reef, but as Esper smashed through waves and tipped over further, I struggled to furl anything. Instead I tried the front sail, which was already reefed. I spent the next half an hour, slowly creeping around the deck, first one side, then the other, to bring that sail in. Hundreds of tons of water washed down the decks and half the tow-rail disappeared under the sea. Getting into a safe position to winch was hard enough, let alone trying to furl away a sail tight as a drum, but Liz and I had done this before and knew that, if nothing else, Esper would look after us. The battering lasted over an hour, though exactly how long I’ve no idea.

Esper did indeed look after us, but we didn’t look after her:

Initial Damage

The squall had ripped off our port-side jerry can board, taking two full drums of diesel over the side, and the bar that holds up our solar panels took a pounding and bent.

- The deck hatch above the saloon had a broken catch and was letting in sea-water by the bucket-load. Salt water was running across the ceiling and down the walls, soaking books, pictures, shelves, sofas, cushions and the floor.

- A broken automatic bilge switch meant the bilge pump wasn’t coming on. We were filling so quickly that oily water was rising up through the floor, staining and delaminating our beautiful oak boards, making walking slippery and dangerous.

- The rear heads (toilet) were letting in water from somewhere and the floor was filling with brown liquid.

- Lighting circuits were getting wet so the galley lights flashed intermittently.

- Finally the water that had run down our walls was literally peeling away our oak laminate like wall-paper.

Esper’s interior aged ten years in two hours.

Millie, meanwhile, had found the smallest, tightest hole in the rear cabin, tucked herself in and fallen asleep. I wished I could have done the same.

The Bigger Problem

Esper’s interior wasn’t top of our minds.

She’d been pushed into the One and a Half Degree Channel, roughly where the Northern Equatorial Current begins. Now we had bigger problems.

Added to the west wind pushing us east, we now had a current coming from the west also pushing us east. The current alone travels at three knots or more, whilst the strong winds had us sailing at over six knots. Basically we were heading nine knots in the wrong direction, and when I mean wrong direction I mean out into the open sea, away from the lee of the atolls and away from our destination.

Below is a screen grab of our track, which had us sailing in a perfect south-easterly direction throughout the squall.

The Moment Of Terror

Now imagine this: you’ve been knocked off course so you need to steer the boat roughly south-west, which would be approx 210° on the compass. Moving the boat round to point in this direction (your ‘heading’), you notice your course over ground (actual direction of movement) is reading 080°. You’re pointing south-west and moving east. You move the boat round to counter this so your heading is 270° (west), and now you’re moving south-east. Now add in the wind factor and at certain points on the compass we’re travelling at over 3 knots, sometimes 5 knots, in the opposite direction we want to go. Basically, we’re moving backwards.

The radio crackled into life: “Esper, Esper, this is Divanty. Are your instruments ok? I seem to be having problems with some of my readings.”

This was the moment of terror. The heading of the boat bore no relationship whatsoever to the actual direction we were moving in. The current we were caught in, combined with the winds, were so strong we simply could not steer anywhere on the compass between 180° and 000°. I almost threw up with the sudden realisation that the squall had knocked us so far off course we were now, essentially, adrift.

Hell: Day One

After the squall died down (it continued with confused seas and strong winds) our immediate reaction was to get back into a close-hauled position and point as south-west as possible, but that eastern current just kept pointing us south-east. We tried every angle of wind, every sail combination, and tried using the engine to power us through the current.

Watching our course-over-ground and our speed over ground, the display would flash up “140°, 3 kn”, which was not what we wanted to see. One hundred and forty degrees would have us sailing past the south west tip of Australia! Often the display would show “060°, 3kn”, which would have taken us to southern Sri Lanka.

By sheer cunning and clever helming we occasionally saw us heading “190°, 0.5kn” which, if we could hold that course, might have us hitting the southern tip of the next atoll in five days time. But we simply couldn’t hold it and the display once again flashed up “080°, 4kn”.

From hereon in we were hand-steering, taking it in turns to battle with the helm., an exhausting process, especially when you know it will not change for a while. The last forecast I’d downloaded had sustained winds of 20 knots for the next five days. Despite this, your body kicks into survival mode and starts to draw on energy through adrenaline you never knew you had (and fat stores you knew you had).

The first few hours were spent trying to reach North Huvadhoo atoll, but we were motoring hard and only making 0.5 knots against the current.

Then the next Force 8 squall came.

We smashed into the waves, taking more water on board and trying hard to hold a course, riding over rising seas, but it was a losing battle. We continued to move south east.

The most gut-wrenching thing was this: for every hour of hard motor-sailing in some kind of south-westerly direction, each squall that came along pushed us back to the same spot. The squalls were relentless, one after another, and the situation was getting desperate. I managed a grimace when I thought of people’s comments on Facebook, jealously reminding us we were sailing in paradise. With no land in sight, miserable skies and a large, dark swell in seas 2km deep, it wasn’t what I had in mind when setting out to sail the Maldives.

One squall had all the lines on the foresails left in a knotted, frayed mess. Seeing the next squall approaching I had to untie it all in order to use the foresails for some kind of stability.

Not thinking of the consequences I clambered forward without safety harness or life-jacket and spent half an hour trying to untie it all. Liz, meanwhile, was in the cockpit screaming at me to come back and, when eventually I did, she shouted at me never, ever to leave the cockpit again without my life-jacket.

It was a desperate situation because had I not untied those knots we’d have probably ripped the foresails altogether, so safety went out the window, but that was the last time I left the cockpit unharnessed.

We knew that to head anywhere south was completely futile, so we made the difficult decision to turn around and head back to one of the northern atolls and maybe try again.

Liz checked in on Millie, who wasn’t exactly pleased with the situation either. She grabbed Liz’s attention, nuzzling her and looking for comfort, but she soon settled once she’d been fed and hid under the pile of clothes spread across the cabin. The clothes rail had come down and it was a mess, but it provided comfort for Millie. The skies darkened and choppy 4-5m waves turned a murky green. We looked for glimmers of hope. A cargo ship, perhaps, or a radio mast on an island. There was nothing. We were in no-man’s land and we were moving deeper into it.

Help us put out more quality work,

become an FTB MATE!

It costs less than a cuppa tea…☕

Hell: Day Two

The next twenty four hours were probably the worst.

We had been motor-sailing hard into the wind and current in order to make any progress, but we were being pushed further away from land.

Now we contemplated changing course altogether. There were a number of options:

- Try to get an angle for Malaysia – we’d probably have enough provisions but we had no charts for the area

- Sri Lanka could have been possible, but we knew that the weather system there was pretty terrible

- Keep heading south to reach the southern equatorial current which would then push us west again. But the last weather report was showing south-westerlies there too.

- Find a comfortable point of sail and just go with it (or heave-to) – but we had no idea where we would end up (Australia?)

No, we had to head back to the closest possible atoll.

The storms kept coming. Every squall brought winds of 36+kts and just pushed us further back. Each time we achieved some vaguely northerly progress, another squall pushed us in the wrong direction.

We’d lost contact with SY Divanty after the first night, making broken radio contact with them in the morning to agree that we would continue to head south. We had no idea where they were, imagining that with a bigger boat and bigger engine they’d probably be on Huvadhoo atoll by now. We were happy for them but it depressed us further to know our 60hp Perkins engine had failed us. (Unbeknown to us at the time, Divanty, with their 135hp engine and larger boat, were stuck in the same situation.)

With rolling easterly swells and wind whipping up spray across the deck, we’d smashed through the waves and made some kind of slow and frustrating north-easterly progress, hoping that the winds would change.

As night came we were hit by yet another squall.

At this point everything tied to the deck had slipped, moved or gone overboard. Our folding dinghy was now sliding into the water, scooping up gallons of sea and threatening to take out all the stanchion posts on our starboard side. I had to go forward and lift it back on deck, so with Liz screaming at me once more, I found myself on a bucking bow, drenched by every wave Esper rode. It was tough work but I managed to secure the Portabote, and picked up more cuts, bruises and bangs to my already battered body.

The next squall created problems with the foresail. It was stuck and we couldn’t furl it. About a quarter of it remained unfurled and was actually quite useful in providing a little forward drive, but it was going to prove dangerous at some point.

Hell: Day Three

At one in the morning, in a night of what seemed like one single relentless storm, the foresail unfurled itself. Fortunately it wasn’t blowing thirty knots so I went to the foredeck to see if I could sort the furling line once and for all, only to find there wasn’t one! The furling line had got caught and over a few hours had chafed, releasing the tension on the furling drum, allowing the sail to open. There was only one thing for it: drop the halyard (the line that holds up the sail) and bring the sail onto the boat.

The next hour, leaving Esper to drift further east, Liz and I battled with the sail. At the mast, Liz would lower the halyard a little as I tried with all my might on the bow not to let it fall into the water. It came down eventually, but was now twisted around the forestay (forward cable that the sail is attached to), and the lines were knotted and wrapped around it too.

It took us an hour to get that sail into the forepeak and we count our lucky stars that the sea at that point was not coming over the deck and into the open hatch. Not that it would have made any difference to our now soaking interior.

Seeing Stars And Other Things

I was fit to collapse. I cannot describe the level of exhaustion we were feeling and we both needed to rest just for five minutes. We contemplated heaving-to, but we were worried about being pushed further offshore and losing all the ground we’d made.

Liz, who had gone down below for a pee, came up in floods of tears. I thought something terrible had happened to Millie and felt sick with anticipation at what she was going to tell me. Liz, however, had slipped on the oily floor as Esper lurched sideways, and banged her head so hard she saw purple stars, just like a cartoon character. She was thoroughly pissed off.

Auditory hallucinations had started two days ago but now we were getting visual hallucinations too. Staring at a red-lit compass, concentrating on not allowing the boat to deviate any more than thirty degrees in twisting seas, takes its toll. Liz started seeing other worlds in the floating, illuminated globe, and the wind indicator was turning into a clown’s face. Meanwhile I could see the cockpit floating in an aquarium with fish and coral, and Christmas tree branches grew from the floor. People were running across the horizon, imaginary islands appeared in the distance and, at one horrible point, another boat, unlit, came along side us.

When a dark, cloaked spectre appeared above Liz’s head at the wheel, I knew it was time to get a grip.

We just needed an hour to rest, but the next squall came.

This one lasted all night. It ripped the bimini (our cockpit cover), smashed off the forward navigation light and had our spare dinghy sliding around the foredeck. It had been lashed down with cargo straps and tied at six points.

Meanwhile, down below, I had to empty the flooding toilet by hand, regularly pump the bilges to prevent more oily water drenching our floors, all the while checking our track on the computer to see our progress. It just depressed us further.

But at no point did we ever give up, we knew there would be an end to it at some point, we just needed to get through it. I realised I hadn’t written a log entry for two days, a subconscious way of forgetting the past and dealing only with each new situation as it presented itself to us.

Dawn arrived, but daylight offered little comfort. I cranked up the satphone and called SY Divanty.

ME: “Hi, Anthony, how’s things? Where are you?”

ANT: “I’m not exactly impressed with the situation but we’re all well. We saw your AIS track flash up on our computer and saw that you were heading north. We’re doing the same.”

ME: “You mean you’re not on Huvadhoo?”

ANT: “No! We had her in our sights though. We could see lights on the island but we never got closer than 16 miles away, no matter how many revs I put on the engine.”

It sounded like a Hitchcock film. If Divanty, a well-found S&S designed 52ft Nauticat couldn’t make it, what chance did we have? It was mildly encouraging that they had had a similar experience to us, minus half the mishaps. Not that I would wish this scenario on anyone.

One of the next problems we had to contend with was that the winds were coming round to the north west, precisely the direction we were trying to head in! I’d had enough. I pushed the throttle forward on the engine, taking her close to 3,000 rpm (I rarely go over 2,300), and started to move forwards at a rate of 1 knot. That’s slow walking speed and land was over 40 miles away.

Four days of smashing our way through erratic, lumpy seas, only to be pushed back with every squall? Give me strength.

We continued like this the whole day, burning through fuel at a ridiculous rate but inch-by-inch we were heading behind the lee of the atolls once more and slowly, gradually, the sea state settled.

Day Four: Leaving Hell

Liz and I relaxed a bit.

I ate a whole tin of tuna and together we came up with a great screen-play based on our experience. It was good to keep the spirits up, but despite the ever-presence of the Maldives to the west, we were not out of danger.

As the winds continued to come to the north-west our progress towards land was not as enjoyable as it should have been. We were hammering through gallons of diesel but still only travelling at 2 knots. Still, 2 knots in the right direction was better than none, even though we were only ever so slightly steering just west of north.

The squalls continued.

By now we were used to them and prepared for each one as they arrived, and were able to ride with them and point ourselves in the right direction.

It wasn’t until the morning of day four that we could say we were safe. We had enough power motor-sailing, and enough lee from the atolls that we could, if we wanted to, duck in west to a western atoll for respite. It was tempting, but getting back to Male made more sense.

Millie emerged. Jumping up the companionway and into the cockpit she sniffed the air, surveyed the familiar atolls, and appeared to approve of our progress.

Summary

As I write this it already seems so trivial. I look at the screen shots of our track and it doesn’t seem so bad now.

But it was.

Making that progress west was the biggest struggle I have ever undertaken. I never once doubted Esper’s ability to keep us safe, Liz’s helming skills or my own stamina, but there was a long period when both of us were fearful of what would happen next.

Exhausted, being stuck in an open sea with no control over the boat, with no other boats in the vicinity to come to our aid (this is an empty part of the Indian Ocean) and the only option to sail on a damaged boat in a direction vaguely towards land over 1,500 miles away without charts, was terrifying.

Esper’s Damage Report

Fortunately most of Esper’s damage is cosmetic. Liz and I had always planned overhaul of Esper at some point, so we were philosophical about the destroyed wood.

The foresail furling mechanism, however, needs to be sorted immediately, no matter where we head next.

- broken foresail furling mechanism

- navigation lights over-board

- two jerry cans over-board

- frayed lines

- bent solar panel arm

- ripped bimini

- leaking saloon hatch

- no automatic bilge pump

- floor boards destroyed by oily water

- laminate peeling off the walls

- rear heads flooded

- furnishings soaked in salt water

Personal Damage Report

The human body is an amazing thing. In survival situations it switches onto auto-pilot. Even so, we aged as much as Esper did during these four days and received some harsh, physical punishment for our efforts.

- stomach cramps – Jamie

- bum-wee – Jamie

- sailor’s bum (spots caused by salt water) – both

- heavy bruising – Liz

- cuts, nicks, welts, sores from bare-footed salt-water existence – both

- bump on head and resulting lock-jaw – Liz

- lower back problems – Jamie

- ripped hands – Jamie

- ruffled fur – Millie

Food Consumed by Jamie

I do not recommend this four-day diet.

- Day One: pasta salad

- Day Two: a few mouthfuls of tuna and two chocolate biscuits

- Day Three: two mouthfuls of noodles and a chocolate biscuit with coffee

- Day Four: whole tin of tuna, tea, coffee, biscuits

Lessons Learnt

If nothing else we learnt loads these last few days. Not just about tactics but about ourselves too. I can’t be bothered to turn this into a lessons-learnt article, but here’s a couple to get you going:

- reef for the night, whatever the conditions

- always wear sailing gloves

- beware currents and their effect when combined with changeable wind

- don’t buy a boat

Finally, don’t ever tell a cruiser they are living the dream and sailing in paradise!

Peace and fair winds!

Liz, Jamie and Millie xxx

🎬 SUBSCRIBE TO THE FTB SAILING CHANNEL!

🛒 FTB SHOP – GRAB SOME MERCH!

🤝 BECOME AN FTB MATE!

If none of the above floats your boat, please consider supporting us by clicking an icon below and sharing this post. Cheers!

If you like our content and would like to support us, we will give you ad-free access to our videos before they go live to the public, discounts in our shop, access to Jamie’s iconic full-res photographs, and supporter-only blog posts. Click our ugly mugs for more info!

Amazing what you went through. Good you made it through. Great reading. I laughed at: don’t buy a boat 🙂

Hi Liz and Jamie, very happy that fast forward to today, 21st July 2019, follow the boat Esper still continues to sail the seas. Now I know why you did the extensive refit on Esper that took a year in Thailand.

I know this is an old post. What a terrifying experience. This should deter me from ever owning a boat but instead I want it more. The danger and adventure I suppose. If I am to compare it to land life – where we face the tax man, road rage, politics you can do nothing about, the boring rat race running for 20 years, one becomes so jaded and a story at sea like yours just makes me want to sail even more. Hopefully, when faced with challenges like this passage you survived – I do as well as the you both did. (including Millie)

Pingback: SAILBOAT REFIT Pt 1: INTERIOR | followtheboat

I have been reading quite a few of your blog posts over the past few days after finding this magnificent website. While this is an old post I cannot help but compliment you on pulling through this situation with your spirit intact.

The excellent writing kept me on the edge of my berth throughout the entire post even though I knew you’d made it through. Thanks for sharing your adventures, good and bad.

I remember a few times when I was praying hard, for just 5 minutes of calm, my hands hurting so bad from having to hold so hard for so long.

Bad weather is just that, bad! I avoid it like the plague, if I can help it. The problem is, sometimes is just unavoidable, and you deal with it. Other people advice is useles in these situations, because they are all different. You just make up your mind, that giving up is not an option, and keep doing your job (even bailing up shit). I remembered a similar situation I was in about 10 years ago. Broke engine clutch, so that was gone, broke the mainsail boom gooseneck, so that was gone, and all of my electronics failed at once. I told God, well, I’ve done everything I know and can, now is on you! We were in a gale about 30 miles out close to the Gulfstream, so we were drifting about 4 kn NE away from where we wanted to go.

Finally saw a fishing boat, we shot a flare, he towed us out of the stream and radio for a tow for us.

Prayers answered, we were grateful we kept our wits, and never gave up.

Now it doesn’t seem as dramatic as it felt then. Still we’ve learned a lot.

Thank you for your story, and thank you for sharing it without the hope and reassuring feeling you kept at all times

Thanks for telling your story here, Jaime. Yes, the key is never to stop fighting and to keep hold of the idea that it will be over at some point. We learnt to trust in SY Esper and each other. In many ways it was a great experience and I’m glad we went through it. Cheers! Liz

I got here from Jami’s and Liz’ Patreon post.

I’m surprised that Divanty had so much problems. On the other hand, on a cat, you are probably more conservative about reefing and a cat has usually less upwind performance than a mono.

Also, it explains why Sailing Greatcircle recommends to always go for the maximum engine option. They’re a Lagoon 52S, but I think they have on the order of 220 hp…

Thanks for dropping by! SY Divanty is a monohull, albeit with a bloody big engine, haha! But even they struggled. You just can’t push through waves like that without a powerful engine, but at least we held fast while we needed to. In a big sea, or ocean crossing, we would probably heave to and put out a drogue, possible even turn round to keep the waves from behind. It depends so much on the conditions. Cheers!

You both are scarring me! Delos says the people will break before the boat, so you did good! We can fix the cabin, but take care of your bodies!

Hi CWH, great to see you here!

Yes, it was a scary few days! Delos aren’t wrong, and with just the two of us on watch, it meant no time for food or sleep. The main thing is we learnt to trust each other and the boat. Cheers! Liz

Wind and current formidable opponents. Add gear failure to the equation then fatigue and situations become potentially life-changing.

Thanks for sharing your well-written account of a difficult situation.

There was one part in particular that painted a very clear picture in my mind, where you were lowering the foresail after the roller reefing line had snapped/chafed through.

You see I taught sailing skills for twelve years in a wide range of weather conditions (offshore New Zealand).

The yachts had hank on foresails which have some great advantages (especially when you have an excess number of crew at your disposal. Having said that I did sail 9000 miles on a private yacht, two-handed from New Zealand to Canada with hank on sails.

When it came time to replace the roller furling on our own yacht, I didn’t want to lose the advantages of a hank on sail, but also wanted the convenience of roller furling. I did my research, read the forums and agreed with both sides of the fence, the hankers and the furlers.

The furlers liked to be able to reduce sail quickly from the safety of the cockpit. The hankers didn’t trust the systems would work when they most needed them.

I found a rather pricey furling system designed and built in New Zealand that kept both camps happy.

Their “Kiwi Slides” system works as well as any hank on system allowing you to lower the foresail in any weather while still keeping the luff of the sail attached to the forestay, which prevents the wind whipping the main bulk of the sail over the side. You can even load a second smaller sail into the spare slot, which is really handy for changing sails at sea. A feature I used when sailing from New Zealand to Fiji.

The other feature I really liked about the New Zealand Furler was the mechanical pawl that locks the furling drum when reefed, so there is no load on furling line.

I had read so many times of how furling lines had snapped or chafed through, causing one problem to escalate into major and in some cases very expensive situations.

So if your readers are debating if they should use hank on sails or roller furling, or are ready to upgrade, I can highly recommend the Reefrite furling system with Kiwi Slides, http://reefrite.co.nz/

I believe this system would have given you more options and reduced your risk in the difficult situation you found yourself in.

Thank you so much for sharing your real world experience.

Jamie/Liz, I have just read your blog re storm which I missed the first time I read the blog. It was a truly incredible journey and I am reeling still after having just read it. The sea can be relentless and the stamina and tenacity that you both showed was amazing. I have been in a few bad squalls myself and look back in hindsight and think “that wasn’t so bad” but at the time it can be quite scary, what you went through was something else.You guys really are adventurers and I take my hat off to you.

Did you consider at any point deploying a drogue or heaving to? Seems like you became aware of going in circles fairly early on. I just followed links from thinking about India and your great post about Kerala and it turned out to be quite the adventure story.

A drogue would have done nothing, Sam. We had a consistent current and constant squalls pushing us in the wrong direction. There’s loads of stuff in Kerala, btw. Just use the search facility. Thanks for dropping by!

Awesome storm story! I know being out there sucks…I hate being able to see where I need to get but not being able to get there due to wind and currents. Happened to me recently off of Cat Is. in the Bahamas, but luckily the squall only lasted for a night before we could spend a full day beating against a current to get in and protected. Safe travels!

– CC

Bloody Hell ! ♥

Great pictures Jamie.

Take it easy out there eh? X

what doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger. The boat didn’t let you down and you didn’t let her down. Nothing new broke so you only have to replace old stuff. No matter what you say…you are sailing in paradise. Keep writing these yarns and keep the plebs away. X

Crickey that sounds utterly terrifying. I cannot imagine being able to deal with 5 mins of that let alone 4 days. So glad you are all ok, and hugely full of admiration that you survived it and better still it hasn’t put you off ! Loads of love x

Great storytelling, surely a very unpleasant trip, especially with a stomach bug. You have everybody on the edge of their seats with talk of near gales, storm tactics and failing equipment.

What you are really describing is poor maintenance, poor preparation (hatches open at sea?) poor passage planning, with the miles you’ve racked up you really should know better.

The ops are right if this is how you carry on it would be safest to sell the boat and write fiction novels from an armchair.

That’s absolutely correct. We broke the latch on purpose and left the hatch open to let in the glorious sun.

Armchair sailors. Don’t you just love ’em!

Honestly you guys make such a fuss about things – I’ve had worse nights out in London 😉

Seriously, glad you (and more importantly, Millie) made it through. Just remember the old saying “that which doesn’t kill you just really pisses you off.”

Love to you both

Mat & Ali xx

What a tale! Jamie you had me reading without a breath. It’s hard to imagine what you and Liz have been through.

I’m so glad you’re safe.

Where’s your book of travellers’ tales?

Wow, sounds like a quite an ordeal. I hope your next few trips are slightly less eventful.

Glad to hear that you’re all safe.

Whoa! Ive just had the time to sit and read of your dreadful trip. All I can say is extreme respect! Never again will I tempt fate by telling you you are in paradise. Just because I was on Kihavah I assumed, quite wrongly it really was a paradise. Just goes to show how (obviously) totally different things are at sea. I am sitting here going over things you experienced and I don’t know how you managed. Masses of experience, faith in each other, your boat and your abilities. I’m so glad I’m able to write this to you both ’cause it means you made it through. Well bloody done all of you – Esper included. Two things cross my mind, how in heavens name would just one of you managed had it come to it and how in heavens name did you brew tea!!? Much love Susie xx

Good Grief!

Now I know why I don’t trust things that float in big ponds. Once went trough Drakes Passage on a 2,000 ton boat in a force nine and swore then that I’d never go further than the Isle of White on a little one like Esper. Hope that she and both of you are back to best health soon. Safe sailing.

Peter

Good Grief!

Now I know why I don’t trust things that float in big ponds. Once went trough Drakes Passage on a 2,000 ton boat in a force nine and swore then that I’d never go further than the Isle of White on a little one like Esper. Hope that she and you are back to best health soon. Safe sailing.

Peter

Top job guys, shows how quickly it can go away tad pear shaped. We are very impressed by the way you both coped, and just got on with it.

Esper will shine again, keep a few of the scars in the saloon though as talking points.! Love the blog and writing style.

Once again great response to a tough situation. Kind regards and happy refitting Colin

Emerald

Top job guys, shows how quickly it can go away tad pear shaped. We are very impressed by the way you both coped, and just got on with it. Esper will shine again, keep a few of the scars in the saloon though as talking points.! Love the blog and writing style. Once again great response to a tough situation. Kind regards and happy refitting Colin

Emerald

Jamie,

Please don’t leave the cockpit in a storm situation without a life jacket, and preferably a harness. It would be such a shame if you were lost overboard and as a consequence stopped sending us these great tales from the high seas. Seriously though, hats off to you two. You’ve both come such along way since you first arrived in Bodrum marina with Esper.

Be safe and keep those tales coming!

Jon x

We wouldn’t have progressed this far were it not for your expert tuition in Turkey, Jon. I don’t remember us doing storm tactics but we appreciate your help otherwise! Wishing you and the family well.

Wow!! Without a doubt, the most gripping account of your sailing yet, I mentally gave up somewhere on Day 2..imagining myself losing sanity and rocking in a corner of the saloon. I guess you have now experienced the ultimate challenge and you survived, with faith, focus and unfathomable friendship. Shame about the damage to Esper, but glad Millie lived to tell the tale.

Jamie and Liz,

Liz will do anything for a good story!

Seriously you two. Be proud of yourselves for looking after each other in horrific conditions/

I got hallucinations after two days sailing and they are not good especially with everything else.

It is hard to put into writing just how horrendous it is to be stuck in a bad sea but those of us who have been through it know. You did good.

Thank you to everyone for your kind comments, we always love hearing from you. No, we will not be selling the boat! These are still the early days of our adventures at sea. We learn from our experiences and hopefully make us better sailors. Lots of love from Male.

Oh dear, it did not take long for you to have me distraught! My first reaction was the same as Fiona’s, but I realise that would be in vain. All I can do is keep my fingers firmly crossed. I’ll come back again when I have had a chance to reflect on all this.

Reflect on the fact your daughter is safe, Henry. Esper and I look after her, though Millie provides the most comfort!

Bloody hell! What a truly horrific experience. I can’t begin to imagine how you held on to your nerve or your sanity…but you obviously did. Certainly brings home how valuable experience, knowledge and resilience are!! Ver sad to see the damage but, as you seem to have accepted, that’s ‘only’ ‘stuff’. You’re alive and relatively intact…and both Esper and all of you sound like you’re ready for some TLC. Make sure you ALL get some!

The forces of Nature are indeed amazing and frightening and I am very thankful that you are safe after reading the story of your hair-raising ordeal. Incredibly, whilst engrossed in your learning of your dilemmas all of a sudden everything under me and around me started moving . . . yes, it was a mild earthquake here in southern Ontario that seems to have originated just north-west of Ottawa! Seriously, I thought I was in tune with you on those seas but without the brutal winds.

One of the things I have learned from you as I have truly enjoyed reading your blogs is that you are amazingly resilient and optimistic! I admire you both so much! I am soooooooo impressed with the manner in which you have handled situations and issues that would knock most of the people I know – myself included – off their feet! Bravo! a million fold!

I hope you are in a safe place where you can make the necessary repairs and are able to continue on your voyage again when you are both ready. Much love to all.

Thank you very much for sharing your survival story so vividly!

Thank you, Connie. We love sharing our stories, especially with you! Repair plans are already afoot.

Well what can we say. Have just come into Hotel study in Puglia to check E-Mails, after a wonderful hot, sunny day cycling in the beautiful Italian countryside. We wish we had not read the blog until we got home. Thank God you are both safe and Millie has forgiven you. Our wonderful stay on Esper is a distant memory, now reality kicks in. Our love to the three of you and PLEASE take care..

Dear Ma and Pa. You of all people know how solid Esper is. As long as we stay with her, we will always be safe. Now get back to your cycling and enjoy that beautiful countryside! Lots of love xxx

So pleased that you and Liz have lived to tell the tale! My husband (who never reads ‘travel’ related stuff online) was glued to the screen. Your story had the pace of a thriller. Made fantastic reading – but horrendous to have lived through this. I’m so glad you are both safe and sound. x

Do us a favour Cuz and Cuz in law, sell the boat and come back home! I don’t think I can read another blog like that again. As much I as say i’m jealous of your lifestyle, reading this has made me realise how dangerous sailing can be. Keep safe. Love you both loads. Fx

Wow, have been riveted to the screen reading your account Jamie. Glad you are both safe but so sorry Esper suffered so much. Here’s to Millie who knows all the good hidey-holes. Take care and please stay safe xx

Wow, what an experience. Sure glad everything turned out okay

hi guys, glad to hear the ordeal is now over,,,, take heed and rest and rub those bruises……and take time to restore esper to her glory….. sailing is supposed to be fun…. 🙂 even i wouldnt have enjoyed what you have just gone through….. take care and see you soon, love nick and sarah x

Wow. So glad you guys survived. Can I add, “close the hatch” to the list? (Although not sure that would have helped the floor with the heads broken.) What a shame Esper is in such a state. Hope you get some much needed rest and settle somewhere for a little while to make the necessary repairs. x

Thanks, Kat. We see this is the perfect opportunity to refurbish Esper the way we always wanted to! Hope you and Olly are well xxx