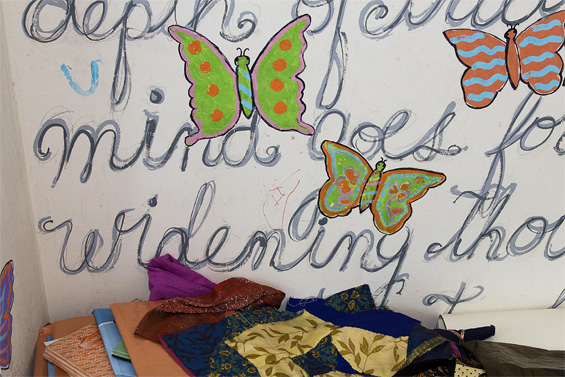

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where the mind goes forward into ever-widening thought and action.

Into that heaven, let me awake.

The words of Rabindranath Tagore are writ large – in rainbow colours and block letters filled with patterns – across one of the classrooms at Durag Niwas. Flitting through and around the multicoloured ABCs on the opposite wall are brightly painted butterflies. We are in the heart of the Sambhali Trust.

Now an embattled 27 year old, Govind Rathore (left) set up the Trust when he was just 23. His first-hand experience of seeing women treated as second-class people with no rights, led to his “dedication” to the empowerment of women in Rajasthan.

Now an embattled 27 year old, Govind Rathore (left) set up the Trust when he was just 23. His first-hand experience of seeing women treated as second-class people with no rights, led to his “dedication” to the empowerment of women in Rajasthan.

We were in Rajasthan when the 2011 census was underway in India. According to the state’s Subhra Singh, Joint Secretary and Director of Census Operations, “The census of 2001 had brought out many striking figures. It had concluded that there are no women in 74 villages, there are no women workers in 647 villages, women literacy is zero in 633 villages, there is no girl child between the age of zero to 6 years in 533 villages and the sex ratio in 14,204 villages is less than 900. Therefore, this year we will be focusing more on women to bring out the truth in these figures.”

We were in Rajasthan when the 2011 census was underway in India. According to the state’s Subhra Singh, Joint Secretary and Director of Census Operations, “The census of 2001 had brought out many striking figures. It had concluded that there are no women in 74 villages, there are no women workers in 647 villages, women literacy is zero in 633 villages, there is no girl child between the age of zero to 6 years in 533 villages and the sex ratio in 14,204 villages is less than 900. Therefore, this year we will be focusing more on women to bring out the truth in these figures.”

In some villages there were simply no women? In the areas where women were counted their numbers were so low it seems there were far fewer females than males. Would it be better in 2011?

The recent 2011 Provisional Census figures for Rajasthan show an alarming drop in sex ratio in the 0-6 age group from 909 in 2001 to 883 in 2011. “A decline of 26 points is indicative of a clear bias against the girl child in a cultural milieu mediated by a range of factors – a feudal history, stringent patriarchy, rigid gender norms and deep-rooted disadvantages which pervade all spheres of domestic and social life.”

The recent 2011 Provisional Census figures for Rajasthan show an alarming drop in sex ratio in the 0-6 age group from 909 in 2001 to 883 in 2011. “A decline of 26 points is indicative of a clear bias against the girl child in a cultural milieu mediated by a range of factors – a feudal history, stringent patriarchy, rigid gender norms and deep-rooted disadvantages which pervade all spheres of domestic and social life.”

Kanchan Mathur and Shobhita Rajagopal, from the Institute of Development Studies in Jaipur, goes on, “The use of ultrasound technology to reject the unwanted girl child has become widespread in the state. This came to light in 2006 when a sting operation carried out by the Sahara television channel captured on camera over a hundred doctors across 22 districts violating the law. More cases of female foeticide have been unearthed since then in various parts of the state.”

Kanchan Mathur and Shobhita Rajagopal, from the Institute of Development Studies in Jaipur, goes on, “The use of ultrasound technology to reject the unwanted girl child has become widespread in the state. This came to light in 2006 when a sting operation carried out by the Sahara television channel captured on camera over a hundred doctors across 22 districts violating the law. More cases of female foeticide have been unearthed since then in various parts of the state.”

Rajasthan’s women, if they survive birth, spend their lives working for no pay, uneducated, often brutalised and usually hungry. Despite rapid growth, India lets its girls die. “First the husband is seated and fed, then the brothers and then whatever is left is fed to the girls… If there are two mangoes in the house, first the boy will get to eat.”

If you are female and a Dalit in Rajastan the odds are stacked even higher against you. Dalits (aka Harijans, Outcastes or Untouchables) are often despised by those of ‘higher’ castes.

If you are female and a Dalit in Rajastan the odds are stacked even higher against you. Dalits (aka Harijans, Outcastes or Untouchables) are often despised by those of ‘higher’ castes.

“These days,” Govind tells us, “many of my own community will not drink water with me any more because I sit with Dalits.”

Govind carries mace spray with him as he walks the mean streets of Jodhpur looking for girls who may need his help. He says of the caste system, that in theory it no longer exists, “but practically and actually it is very much alive. 70% of India is rural. They say ‘God has given us our castes; God made everyone to fit into their role.’ The government legislates to help Dalits. The government reserves jobs for Dalits. They get jobs as sweepers, but why can’t a Dalit be a teacher?” He says the authorities make the right noises, but it is all “on paper and is not actually happening. It is up to individuals to do something. We must educate and encourage our own communities.”

The Trust’s women – they have ranged in ages from 3 to 65 – are given rudimentary education in reading, writing, geography, health and mathematics as well as skills like tailoring, embroidery, block printing and tie dyeing. Many of them only speak their own dialect, so a basic knowledge of both Hindi and English is essential.

In the census, Rajasthan doesn’t fair much better when it comes to literacy rates. “In 2001, the men’s national literacy rate stood at 75.26% while in Rajasthan the figure was 75.70%. In the 2011 census, while the national men’s literacy rate is 82.14, for Rajasthan it is 80.51, 1.63 below the national average… While the difference between the national literacy rate and those for Rajasthan in 2001 stood at 4.42 points, in the 2011 Census it has increased to 9.98 points. The state’s literacy rate is the third lowest in the country.”

In the census, Rajasthan doesn’t fair much better when it comes to literacy rates. “In 2001, the men’s national literacy rate stood at 75.26% while in Rajasthan the figure was 75.70%. In the 2011 census, while the national men’s literacy rate is 82.14, for Rajasthan it is 80.51, 1.63 below the national average… While the difference between the national literacy rate and those for Rajasthan in 2001 stood at 4.42 points, in the 2011 Census it has increased to 9.98 points. The state’s literacy rate is the third lowest in the country.”

Why so high? Because, although it has increased from the staggeringly low figure of 43.9% in 2001, the current rate of literacy among women in Rajasthan is 52.66%. This is the lowest in India. The national average is 65.46%.

“Sometimes they don’t know how to hold a pencil. They don’t know how to sit properly. Their backgrounds are so awful,” Govind says. “We teach literacy and self-esteem. We teach them about their appearance, good dress sense. Most don’t know where Jodhpur is, or even that they live in Rajasthan. Their lives are simply this: get up, brew tea for Dad, do the dishes, clean the house, cook lunch, sleep, clean the household, make dinner, go to bed. Every single day of their lives. They have no weekends, no holidays. They are married at 15, and then have the exact same life with a husband who probably rapes and certainly beats them. Every girl that comes to us has a terrible life. Women are still killed for their dowries.”

Starting with a few girls from his maid’s village in the desert, the Sambhali Trust has helped over 550 women since it began, four years ago. Govind’s home, Durag Niwas, is a bustling and friendly home-stay for visitors to Jodhpur and the headquarters of the Sambhali Trust. Several of the guest rooms have been given over to volunteers – we meet Annie and Poppy while we are there. We visit the two classrooms on the upper floor of the front building and watch the full time teachers, Simmi and Tamanna, working with the classes. Simmi is a force of nature, teaching them English and the more academic subjects. The class looks by turns terrified and entranced as they watch her every move: they try their best to respond to her, squealing with laughter when she cracks a joke. Tamana is “Didi” their big sister. She is as neat as a pin and all smiles as she sets that day’s lesson in the tailoring class; today they are learning how to sew neck openings.

Starting with a few girls from his maid’s village in the desert, the Sambhali Trust has helped over 550 women since it began, four years ago. Govind’s home, Durag Niwas, is a bustling and friendly home-stay for visitors to Jodhpur and the headquarters of the Sambhali Trust. Several of the guest rooms have been given over to volunteers – we meet Annie and Poppy while we are there. We visit the two classrooms on the upper floor of the front building and watch the full time teachers, Simmi and Tamanna, working with the classes. Simmi is a force of nature, teaching them English and the more academic subjects. The class looks by turns terrified and entranced as they watch her every move: they try their best to respond to her, squealing with laughter when she cracks a joke. Tamana is “Didi” their big sister. She is as neat as a pin and all smiles as she sets that day’s lesson in the tailoring class; today they are learning how to sew neck openings.

Both teachers and girls are part of one big family. The girls confide in their teachers and each other about their terrible situations outside the centre (the Trust has been instrumental in removing some of the younger girls from abusive marriages with their dowries intact). The way the Dalit girls are discriminated against by their neighbours saddens both teachers.

“If a non-Dalit touches a Dalit the person will go home and wash themselves all over. Still, even now,” says Simmi. “The government is trying to eradicate the caste system and help Dalits, but it is entrenched, especially in these less-educated communities.”

More recently Govind has embraced the notion of micro-financing projects for the empowerment of women. He is adamant that through education and investment women will be able to sustain themselves and their children. Most of them have been beaten, abandoned or ostracised from their communities; a large number of them live in the villages in the surrounding desert, where there is no chance for them to survive without some kind of help. He has set up sponsorship opportunities for people to donate funds to the women: a sewing machine or a cow will save a woman’s life. The Trust makes an interest-free loan to the woman who, using her cow or sewing machine, works to pay back the loan. The Trust is then able to re-invest the money into a new loan. A hardy desert cow is one of the most useful assets a woman can have: it costs £150. A sewing machine will cost £50 and give a woman a regular income. If you want to change someone’s fortunes in a big way, you can sponsor a Dalit child through school. For the vast sum of €200 a year for five years, you can change someone’s life.

More recently Govind has embraced the notion of micro-financing projects for the empowerment of women. He is adamant that through education and investment women will be able to sustain themselves and their children. Most of them have been beaten, abandoned or ostracised from their communities; a large number of them live in the villages in the surrounding desert, where there is no chance for them to survive without some kind of help. He has set up sponsorship opportunities for people to donate funds to the women: a sewing machine or a cow will save a woman’s life. The Trust makes an interest-free loan to the woman who, using her cow or sewing machine, works to pay back the loan. The Trust is then able to re-invest the money into a new loan. A hardy desert cow is one of the most useful assets a woman can have: it costs £150. A sewing machine will cost £50 and give a woman a regular income. If you want to change someone’s fortunes in a big way, you can sponsor a Dalit child through school. For the vast sum of €200 a year for five years, you can change someone’s life.

Many of Govind’s friends have become involved in the Trust. Mukta, his wife, runs the home-stay and looks after the affairs of their house. His cousin, Payal, has become an important participant in the project. Married to a proud Rajput man, and living in a beautiful Haveli (nobleman’s house) close to Durag Niwas, she has opened her home as an Empowerment Centre. We visit the classes there and sit in on an English lesson given by Annie. A little reluctant at first, the girls gradually warm up and are soon shouting out their names, ages, likes, dislikes and discussing what they ate for breakfast. Some are shy and one is very cheeky. They are having a good time and you could be forgiven for thinking they live sunny, happy lives like other girls.

Many of Govind’s friends have become involved in the Trust. Mukta, his wife, runs the home-stay and looks after the affairs of their house. His cousin, Payal, has become an important participant in the project. Married to a proud Rajput man, and living in a beautiful Haveli (nobleman’s house) close to Durag Niwas, she has opened her home as an Empowerment Centre. We visit the classes there and sit in on an English lesson given by Annie. A little reluctant at first, the girls gradually warm up and are soon shouting out their names, ages, likes, dislikes and discussing what they ate for breakfast. Some are shy and one is very cheeky. They are having a good time and you could be forgiven for thinking they live sunny, happy lives like other girls.

I discover from Payal that even she, with her high status and financially secure position, lives within the constraints of being a woman in Rajasthan. Her husband works in Jaisalmer, so is away for long periods of time. She cannot leave Jodhpur without him and is expected to behave discreetly in his absence. Luckily, he agrees with Govind that they must work together to improve education and tolerance, and sided with his wife against his mother in opening the centre. Initially uncomfortable with the idea of a house full of Dalits, his mother’s objections were worn down; she now tolerates the good works being done there.

I discover from Payal that even she, with her high status and financially secure position, lives within the constraints of being a woman in Rajasthan. Her husband works in Jaisalmer, so is away for long periods of time. She cannot leave Jodhpur without him and is expected to behave discreetly in his absence. Luckily, he agrees with Govind that they must work together to improve education and tolerance, and sided with his wife against his mother in opening the centre. Initially uncomfortable with the idea of a house full of Dalits, his mother’s objections were worn down; she now tolerates the good works being done there.

We plan to go back to Durag Niwas in December and to visit Govind’s family village of Setrawa, in the desert. I wonder how much more the Trust will have achieved by then? We will report back. In the meantime the Sambhali Trust has a Facebook page. Please click here and show your support by clicking the ‘Like’ button. Thank you!

The Constitution of India guarantees to all Indian women equality, no discrimination by the State, equality of opportunity, equal pay for equal work. In addition, it allows special provisions to be made by the State in favour of women and children, renounces practices derogatory to the dignity of women, and also allows for provisions to be made by the State for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief.

To view the complete set of images taken at the Sambhali Trust, click on the photograph below. After that you may enter ‘full-screen’ mode by clicking on the button with four arrows in the bottom-right of the slide show.

If you like our content and would like to support us, we will give you ad-free access to our videos before they go live to the public, discounts in our shop, access to Jamie’s iconic full-res photographs, and supporter-only blog posts. Click our ugly mugs for more info!

Thanks for uploading my comment. Yes, I know very well that Sambhali is not your charity. The Sambhali trust was set up for the specific purpose of empowering women but in the interview the owner or trustee proclaimed that it’s for “Untouchable” castes Women, aren’t there high castes or mediocre castes poor women in Rajasthan or India?

I think the help should be need dependent not castes or gender dependent.

I have seen the FB profile of sambhali trust owner and he seems to me “Narcissistic”, I like the people like Mandela, Gandhi on his profile but TV programs like “steal your Girlfriend on Channel V” and “M TV Roadies” make me feel very sad and sorry.

How can Save the children discriminates adults? Isn’t adult started save the children program? Male and female is the broad term and we all get fit into it whereas children and adults are two different stages of life.

Thanks again for updating my comment.

PS: I have no intention to defame any individual or NGO, my aim is to show the both sides of the coin and creating awareness.

Who are you to judge what someone likes watching on television in their own time, Nisha? You are not showing both sides of the coin with your comment, you are merely demonstrating the kind of ignorance that makes Govind’s job all the more difficult and it’s a sad fact of life that there will always be people in the world who are down on the goodwill of others. I console myself with the fact that you’ve completely misunderstood the Save The Children analogy, which leads me to think you’re just trolling.

My last comment is not published so I am not sure if truth prevails or not on this blog or not.

Your last comment wasn’t published because we monitor the website as often as we can. Your comment went up this morning. Sometimes we do not have access to the internet, so it gets updated when we are on-line.

To answer your question about “discriminating” against Untouchables. The Sambhali trust was set up for the specific purpose of helping women. There are other charities which help both sexes in the “Untouchable” castes. The Sambhali Trust is not our charity, as we explain in the podcast and online, you can see more about the charity at the Sambhali Trust website. Just because this charity is positively helping females doesn’t mean it is discriminating against males (that argument is about as useful as saying that a charity like “Save the Children” discriminates against adults).

One of the visitors of my blog left a comment –

“You make a living by what you get, but you make a life by what you give.” (Winston Churchill). There is nothing to add to this quote.

more photos if interested-

http://memographer.com/2011/08/incredible-india-sambhali-trust/

Thank you so much, Jamie and Liz, for this wonderful piece of writing and the pictures! Sambhali Trust as a grassroot initiativet really needs this kind of support and publicity.

Well Jamie, I hav to say d pics are very emotive n of course the write up is also very detailed. Somebody who hasn’t visited Sambhali yet can view it completely thru your lenses n Liz’s write up 🙂 …

Ohhh alrite … Kindly convey my best wishes to Liz 🙂

Will do! I do most of the writing but when it comes to our ‘special’ assignments, I stick to the photography and allow the professional writer to take over 😉

Jamie, you have done a wonderful work of bringing up the prevalent issues n letting everyone know what Sambhali is all about. Govind and his entire team is indeed doin a fabulous work n bringing amazing changes in so many lives.

Thanks, Shweta. I should point out that this particular article was written by my partner, Liz.

Thank you once again for bringing many true facts and figures out, a very well thought and put together informative work. We Follow your Boat!

The world needs more people like Govind. He and his wife, Mukta, have done a fantastic job in tackling a very serious and deeply-rooted problem head on, which is why Liz and I fully support the work of the Sambhali Trust.